Rockin’ in Moab

By

Phil Maranda

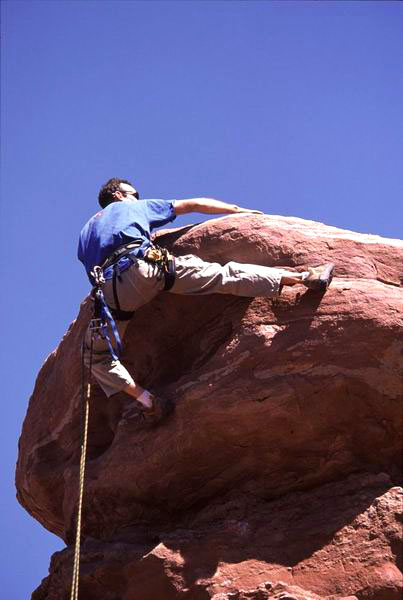

“What the hell am I doing up here?” I want to shout

across the desert. The truth be known, it was my bright idea in the first

place. A simple request I’d made on the phone two weeks earlier

echoes in my mind: “I’d like to take a basic rock climbing

course on my first day and then climb a tower the next.” Now I’m

stuck under a ledge, 150 feet above the ground on a massive tower called

Ancient Art, most of my knuckles white from the strain of hanging on,

others bleeding from smashing my hands on the rock. Sweat pours into my

eyes, my muscles burn, my nerves are shot, and for the life of me, I can’t

figure out how to get around and over the protruding slab of red rock.

-Space-

At first blush the desert drew me in. Its towering pillars, chiselled

canyon walls, and arid climate tantalized my senses as the old Toyota

pick-up bumped and rocked along a winding dirt road up Kane Creek Canyon,

only minutes from the town of Moab. It was there in the heart of Utah’s

red-rock country that I would get my initial taste of free climbing on

rock.

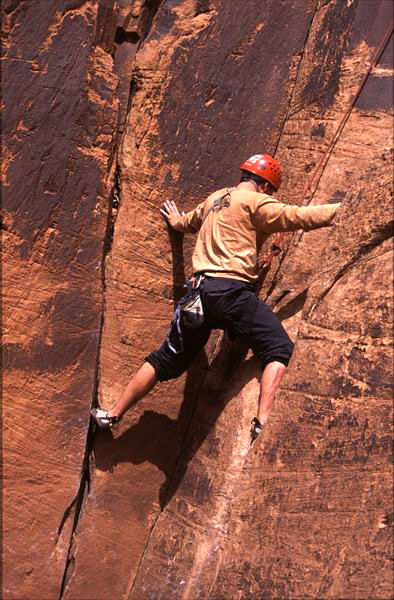

Pulling up to the base of a multi-hued, sandstone cliff face not yet touched

by the early morning sun, my guide, Noah Bigwood, hopped out of the truck

and instructed me to grab my gear. We then began our hike up to a rock

climbing area aptly named Ice Cream Parlor for what I thought must have

been the smooth blend of different hues of reds and oranges in the stone.

Shortly after Bigwood and I scrambled around red boulders, sage bushes,

and pastel green scrub brush and grasses in an ancient landscape so foreign

to me that I might as well have been on the moon, we arrived at our destination.

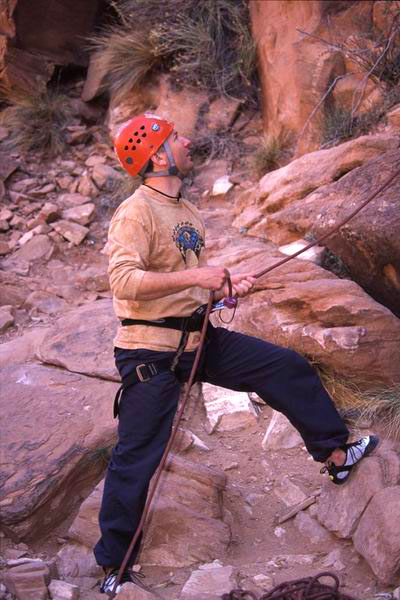

As I eyeballed the polished-looking rock face I’d soon be hanging

on for dear life, Bigwood unpacked the climbing gear and began his pre-climb

instruction. First he mentioned the importance of trusting the equipment,

and then he covered belaying, belay devices, knots, harnesses, locking

carabineers, and his two rock climbing rules—basically all I’d

need to know to get my feet off the ground.

“I have two main rules about rock climbing,” Bigwood said

just before we put on our harnesses and grabbed our gear. “The first

one is that the only reason we do this is because it’s fun. The

second rule, and this relates directly back to the first, is we have to

be safe. If we’re not being safe, it won’t be fun for very

long.”

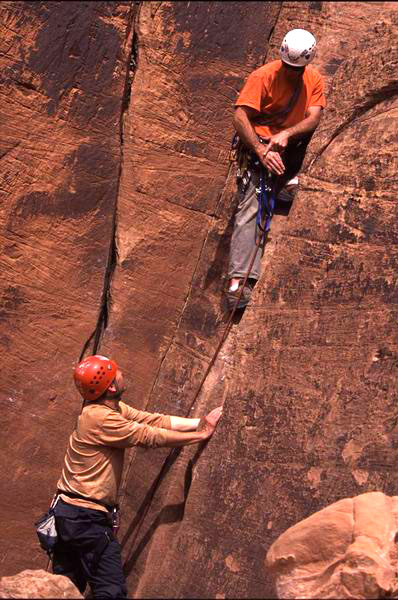

At the wall, it was time to put the theory into practice. Bigwood was

climbing first (lead climbing), and it would be my job to belay him from

the ground. After showing me how he threaded one end of the rope through

his harness and how to tie a doubled up figure-eight knot, he tied another

knot at the end of the rope just beyond the first. “This little

knot can save your life,” he said. “I’ve had two friends

fall because they didn’t tie this knot. If the main knot releases,

this one will stop the rope from sliding right through your harness.”

Bigwood helped me to attach a belay device to my harness by threading

the rope through the device and then locking down the carabineer, an oval-shaped

affair with an opening gate on one side. We then checked and re-checked

our rigs before moving up to the first climb, a 95-foot, ultra-thin crack

in the wall. He motioned for me to stand in a

position where I could hold a fall if I had to and then showed me how

to lock the rope to my hip if an accident did occur. Bigwood gave me the

signal, and I shouted out the commands he had taught me. “You’re

on belay,” I said. “Climbing!” he shouted back from

two feet away. “Climb on,” I replied, and he was gone.

During his climb, my guide placed protection in the form of camming devices

along the crack and called down the different climbing techniques he was

using. Reaching the top, he placed the rope in two bolted metal loops

and informed me he was coming down. Bigwood leaned back into the harness

so his body was at a 45-degree angle to the wall, then walked backwards

while I slowly let the rope slide through the belaying device.

The trick in the rock climbing game is to find an experienced instructor/guide

who’s willing to spend a sufficient amount of quality time with

a rookie. Beginners should become familiar with the equipment and safety

practices in order to feel at ease in the vertical environment associated

with climbing on rock. Bigwood believes that because we spend most of

our lives walking on the ground and even though we do have a history with

the primates of going up, it’s not always as instinctive as it should

be to make the transition from walking to climbing.

Once Bigwood was back on terra firma, we switched roles. He removed the

rope from his harness and attached the belaying device. Under his watchful

eye and further instruction, I threaded the rope through my harness and

then tied my own doubled up figure-eight knot with added safety knot at

the end.

As I moved up to the wall, an ancient fear gripped my body like a vice

and sent butterflies directly to my stomach. To stifle the apprehension,

I took a few deep breaths

and got on with the climb. If I take too long to think about it, I might

jam out right here! I thought to myself.

The first eight feet were surprisingly easy. The crack was wide, there

were lots of handholds to grab onto, and foot placements were readily

available. But when the rift narrowed, the climb changed dramatically.

Suddenly I couldn’t find any handholds, and my feet began to slip

down the slick surface of the rock. Bigwood noticed my predicament and

shouted at me to keep my heels facing downward, allowing as much of the

bottom surface of the shoes as possible to be in contact with the wall.

Next, Bigwood instructed me to kick my toes into the crack, again keeping

my heels down, and trust in the extremely sticky, rubber soles of the

rock-climbing shoes. Once I did that, I felt like an insect stuck to fly

paper, and I found it much easier to climb. The wall instantly seemed

to transform; the crack itself made for excellent handholds, and I was

soon feeling like a pro.

By the time I reached the bolted metal loops that held my lifeline in

place, my breathing, which had been short and frantic during my mishap

on the wall, was back to normal. The butterflies in my stomach had miraculously

vanished into thin air, and I could bask in the satisfaction of making

the climb. Bigwood encouraged me to hang around on the rope awhile, and

I did just that before he belayed me back to flat ground.

After a brief rest—mostly for my feet, which couldn’t get

used to the cramped feeling of the shoes—it was time to attack the

center face of Ice Cream Parlor, which was then drenched by the hot sun.

The route had a plethora of handholds and foot placements and seemed like

it would be much easier than the crack. As it turned out, it was, and

before long, with Bigwood’s help, I had put the center face behind

me and was looking forward to challenging what appeared to be the toughest

climb of the day.

We moved up to the corner crack, and Bigwood mentioned that he wanted

to teach me some of the rope and other skills that I’d need the

following day. “On the tower our 200-foot rope won’t be long

enough, so we’re going to tie two ropes together, especially when

we repel from the top,” Bigwood said.

He grabbed two ropes, giving himself a foot of length with each one, and

tied the ropes together using a square knot in the center and then adding

two fisherman’s knots, one on either side of the main knot. “The

idea behind the extra knots is for additional safety just like when we

tied the ropes to our harnesses,” Bigwood explained. “The

square knot alone is stronger than the rope itself.”

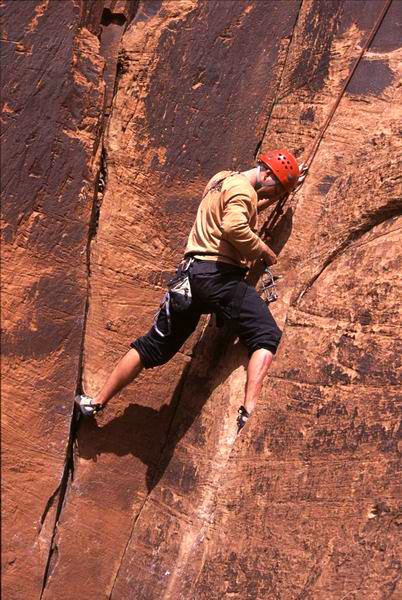

Climbing the 70-foot corner crack required techniques that weren’t

necessary on the first two climbs. Right off, the crack was at the center

of two converging walls, each with cracks of their own. The main rift

was wide and deep enough to use a technique Bigwood called a hand jam.

When he got a few feet above my head, he demonstrated the jam and explained

that I needed to thrust my hand into the crack as far as it would go and

then make a roof shape with my hand.

Next, my guide showed me how to place and remove camming devices. These

valuable and perhaps the most sophisticated pieces of all the climbing

gear are typically made up of four individual cams that are pushed into

a crack in the rock. A trigger system on the other side of the device

is released, and the cams open back up, securing into the crack. The trigger

is also used to contract and release the cams when the need arises.

With the instruction finished for the time being, Bigwood made the ascent

to the top, secured himself in, and shouted down, “You’re

on belay!” During this climb he was belaying me from the top in

the same manner we’d be using on the tower. After exchanging the

appropriate verbal responses, I began scaling the wall.

The techniques I learned came in handy. I found myself negotiating the

crack with relative ease, kicking the toes of my climbing shoes into the

cracks on either side of the main rift, using the hand jams, and even

stopping to remove the camming devices—another skill I’d need

on the tower—before continuing upward.

At the top of the corner crack, Bigwood helped me set up for the final

technique I’d learn that day—repelling. We would use the belay

device in a similar fashion to belaying, only without assistance, and

each of us would control our own descents. Bigwood went first, leaning

back into his harness like it was a chair. He jumped backward, flew through

the air, made contact with the wall, and then repeated the maneuver a

couple times before reaching the ground.

When it was my turn, I leaned back over the edge of the cliff, allowing

my body to sink into the harness, and then slowly walked backwards. Although

my descent was jerky from a lack of control over how the rope slid through

my hands, I did make it to the bottom without smacking any part of my

body on the wall. The overall feeling of accomplishment for a day of climbing

well done stayed with me long after we’d packed up and headed back

to Moab for the evening.

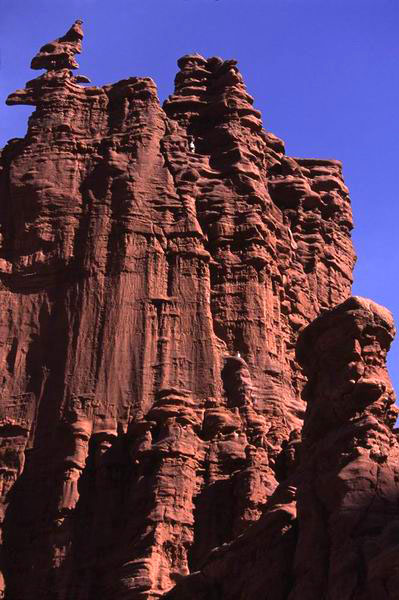

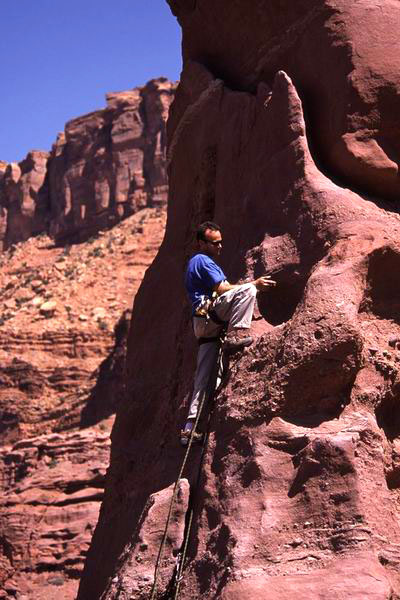

The following morning we set out early for the Ancient Art tower, heading

northeast into the desert, flanking the Colorado River. When we arrived

at the parking area, we could see Ancient Art in the distance, rising

up 550 feet from the desert floor. The

staggered tiers of its summit clearly displayed where the name was derived

from. Before we even hopped out of the Toyota, my apprehension—which

had been building since the night before—reached into the overload

range, and I could feel my heart pounding in my chest. I don’t think

I’m ready for this, I thought to myself as we began our hike towards

the tower.

Looking up to the top of Ancient Art from its base didn’t ease my

nerves any. The tower appeared big enough from the parking area, but from

where I was standing, it looked absolutely massive. Bigwood must have

noticed my fear because he had us climbing within minutes.

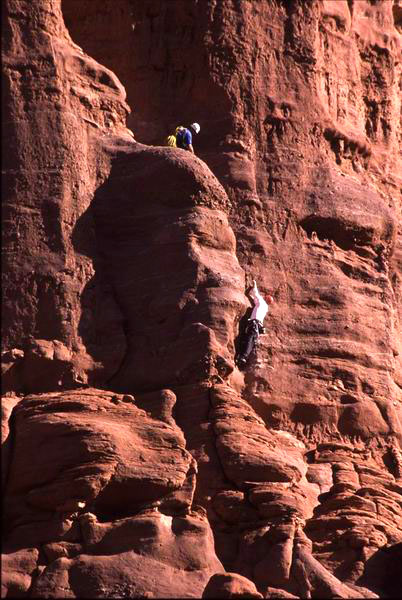

The first 50 feet of the tower was similar to the climbing I’d done

the previous day, but then it changed—the handholds and foot placements

seemed to disappear like a mirage in the desert, and the route became

extremely difficult. Shortly after that, it became impossible for me.

Luckily Bigwood had brought étriers (climbing ladders) and had

set one in place during his ascent exactly where my limited skills would

allow me to continue no further.

Directly above me Bigwood called down and instructed me to place my feet

into the rungs of the ladder and push upward. Despite hitting my knuckles

on the wall a few times, the ladder, along with the little notches that

kept the section of rock from being completely smooth, allowed me to finally

scramble to the ledge where Bigwood waited.

The next section we’d climb would force Bigwood and me to be separated

and out of each other’s sight for a long period of time. With my

apprehension at peak levels, I tried to listen to my guide’s final

instruction and then watched him climb until he disappeared around an

overhanging ledge 75 feet above my location.

Once Bigwood was secured in a lofty position150 feet above me, I heard

him call down that I was on belay. “Climbing!” I shouted back

and began my ascent. At first the climb was going okay; I used the techniques

from the day before—hand jams, kicking my shoes into cracks, trying

to control my breathing, looking around for handholds and foot placements,

and relaxing when things got tough.

Further along l found that despite all of Bigwood’s excellent instruction

and encouragement, the rock was beating me. My body ached, my fear built

with each inch of progress, and my hands and feet were slipping. Finally

I managed to scratch my way up to the overhanging ledge Bigwood had made

short work of during his climb. Looking around I couldn’t see anywhere

to place my hands or feet. The panic elevated to a level that I could

no longer bear. I felt completely encased in rock.

-Space-

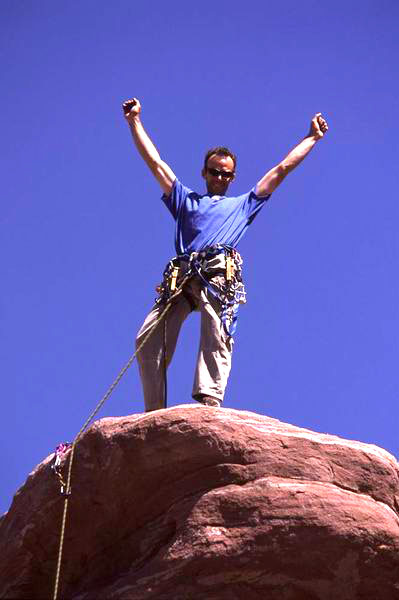

As far as I can tell, there is absolutely no way for me to get around

and on top of the ledge. Defeated, I shout up at Bigwood, “I’ve

got to go down!” He wants to know if I’m sure, and I shout

back that I am. Bigwood then lowers me to where I can later safely repel

and says that he will be down as soon as the other climbers who are on

the tower today make their own repels.

After what seems like forever, the two climbers repel past me, and Bigwood

arrives at my position. I’m finally going to be able to make my

descent. The repel happens quickly as I lie back in the harness and allow

myself to float back to the safety of the desert floor. I’m the

last one off the tower, but that doesn’t matter to me, because in

my case, repelling is a much more enjoyable experience than climbing and

being back on the ground feels even better.

On the way back to the truck, Bigwood mentions that even he has to abandon

climbs from time to time because he has reached his limit. “That’s

how you improve at

rock climbing,” he says. “You keep doing climbs that are slightly

above your level until you can overcome them.”

By the time we get back to Moab, my bruised ego has slightly mended. Leaving

Utah in the distance the next morning, I vow that when I get home, I’ll

attempt climbing on the cliffs there….

On the sheer, vertical rock overlooking the valley I call home, I finally

manage to climb to the top of a fairly difficult route sans the overhanging

ledges.

End

Photography: Phil Maranda

Tracey and I both got the chance to make images during the rock climbing

assignment which was a special treat for we don’t get the chance

to work together on big assignments very often—I usually have to

go those alone. Having two photographers doing the shooting also really

helped me out. It’s just one less thing to think about when you’re

convinced that the Reaper is looking over your shoulder, laughing manically

over the foolishness of your actions.

Besides the blazing sun, red dust, dry heat, and vertical environment

associated with climbing in the Moab area, the photography part of our

experience came off without a hitch. Improvisation was the key to shooting

in the desert: when we arrived at the first wall which happened to be

lying in shadow on a bright sunny day, we used a Tiffen 812 warming filter

to compensate; then as the sun broke over the ridge, we slapped a polarizer

on the lens to try and tone down the glare a little and bring out the

colors. When we discovered that I’d left the tripod mounting plate

for our Nikkor 80-400mm VR lens 1500 miles away, we used the tripod collar

on its own. Luckily we had a Kaiser ball head on our Gitzo carbon-fiber

tripod that allowed us to secure the lens by literally clamping the tripod

collar to the ball head where the mounting plate usually goes. It worked,

but it isn’t advisable.

Tracey Lalonde

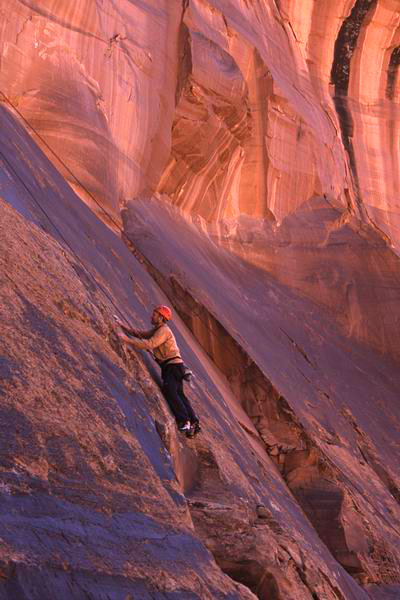

For the distant shots of Ancient Art tower and the climbers, I found a

really great vantage point down in the desert on a giant rock not too

far from the base of the tower. There, I set up the Gitzo carbon-fibre

tripod and the Nikon F100 with Nikkor 80-400mm VR lens. As Phil and Noah

came into view, about a third of the way up, I was able to capture their

climb at various stages up the tower and also give a sense of environment,

at times including the entire tower in the shot. I could then show the

immense size of Ancient Art in relation to the climbers. This, I feel,

allows viewers to experience the scene from my vantage point but also

have an idea how the climbers themselves must have felt during the climb.

Because the climbing took place early in the day, I had some beautiful

morning light to work with. As it was spring, I didn’t have much

of a problem with strong sunlight (which I kept my back to) once the sun

was higher in the sky, but I did use a polarizer.

I also had an incredible spot with which to witness the event, and I could

use the telephoto to keep track of where Phil and Noah were climbing—it

brought me close up to them, giving me a sense of being right there each

step of the way (and it had me thanking God I wasn’t actually doing

the climbing!).